Harriet Christina Tytler (1828 to 1907) was a British artist, writer, and a pioneer woman photographer. She was born in Sikraura, Bahraich, India, where her father was an officer in the 3rd Bengal Native Infantry. She was the second wife of Robert Christopher Tytler, a British soldier, naturalist and photographer. Harriet Christina Tytler was well known for her work in photographing and documenting the monuments of Delhi. Mount Harriet in the Andamans is named after her.

Harriet Christina Tytler was introduced to photography by Felix Beato and Dr John Murray of Agra. Robert Christopher Tytler reported that he took up photography in 1858 in order to assist his wife with her desire to record the Red Fort in Delhi. Harriet tried to paint the fort in oils but failed and therefore she took to photography to document the building quickly.

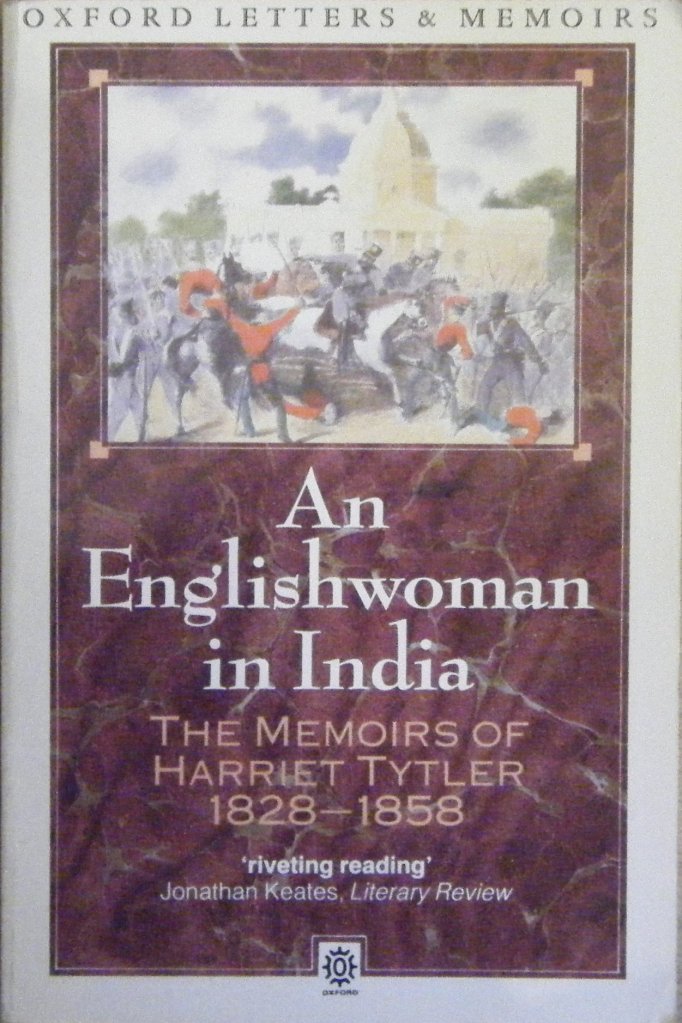

In May 1857 Harriet Christina Tytler and Robert Christopher Tytler were residents in the military cantonments outside Delhi. It was here that Robert Tytler’s regiment, the 38th Bengal Native Infantry, was attack by the mutineers during the great rebellion of that year. Harriet was allowed to stay on because she was pregnant, and making her the only British woman present at the Siege of Delhi. She later gave birth in a donkey cart while escaping to safer areas. She documented eye-witness account of the siege of Delhi, in 1857 in a book titled “An Englishwoman in India: The Memoirs of Harriet Tytler, 1828-1858”.

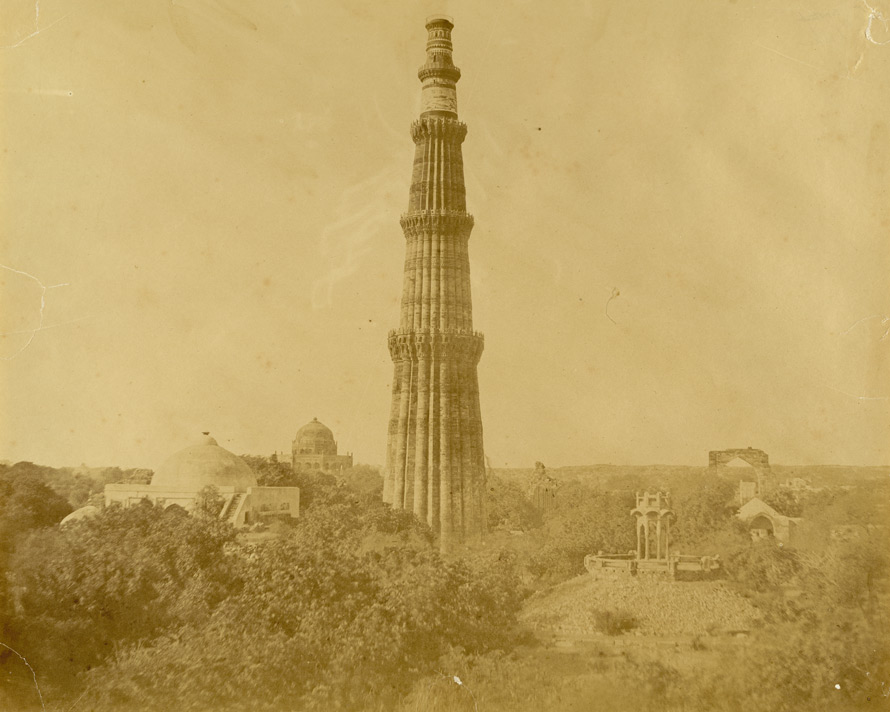

Over several months in 1858, the husband and wife team travelled extensively in Delhi, Kanpur then Cawnpore, Agra and Lucknow, to various towns and places in northern India that had been affected by the 1857 Uprising. She produced a body of work alone or as a joint effort with her spouse Robert Christopher Tytler. This comprised of made about 500 Waxed paper negatives, some of them are three parts panoramas and exhibited them in India and in the Indian office library in London, where they remain today.

Waxed paper negatives were a variant of the calotype process in which the negative was made clearer by waxing the paper before treating it with chemicals.

A dramatic modification to the paper negatives was invented by Jean-Baptiste Gustave Le Gray. Gray was a painting student and a founding member of the first photographic society in the world, the ‘Societe Heliographique’. He saturated the paper with warm wax, resin or oil rendering the paper more translucent. The waxed paper was then “salted” or “iodized”. The prepared paper was stored until ready for total sensitization with silver nitrate. The sensitized paper was exposed through the camera. The exposed negative is developed in gallic acid and fixed.

When Waxed paper negatives, are viewed under normal illumination, the paper can appear waxy shiny with yellow or orange tones overall. When the same negative is viewed thought transmitted light, it gives a sharp, crisp and clear image.

Waxed paper negatives produced a greater definition of the image than the Calotype process but it required a longer exposure time, which is why it was mainly suitable for inanimate subjects such as landscape or architecture.

This Waxed paper negatives gave great advantage and flexibility to Harriet Christina Tytler to travel around and document the landscape, architecture and historical sites around northern India.

The British Library in London and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa holds the two largest collections of the Tytlers’ work.

Reference

https://enacademic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/8095178

Photography: A Cultural History, By Mary Warner Marien,2002, Laurence King Publishing

Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840-1860, By Roger Taylor, Larry John Schaaf, 2007, Metropolitan Museum of Art

http://resources.culturalheritage.org/pmgtopics/1995-volume-six/06_01_Daffner.html

Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, edited by John Hannavy, Publisher: Routledge

Monumental Visions: Architectural Photography in India, 1840-1901, Sophie Gordon, 2010, Department of History of Art, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

http://www.luminous-lint.com/