Benjamin Simpson (1831 – 1923), was a British Surgeon-General and a photographer born in Dublin. He joined the East India Company as an Assistant Surgeon in 1853. He served as the Surgeon-General for the Government of India from 1853 until 1890 and he was prudent advocate of the Empire’s values.

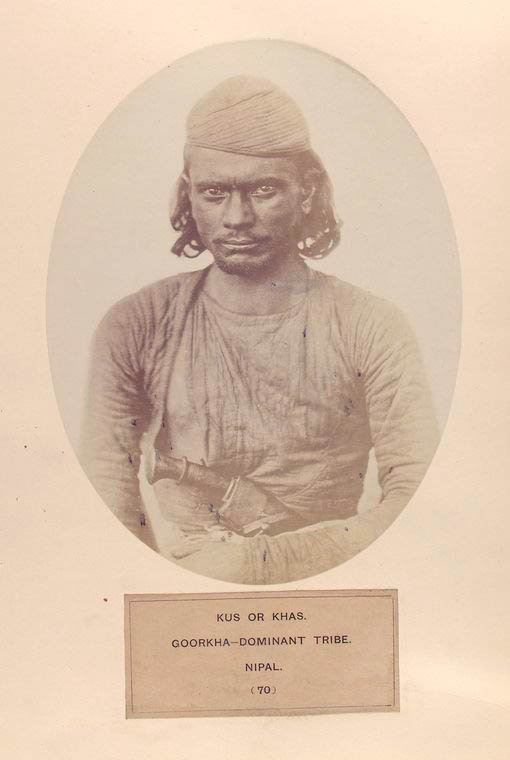

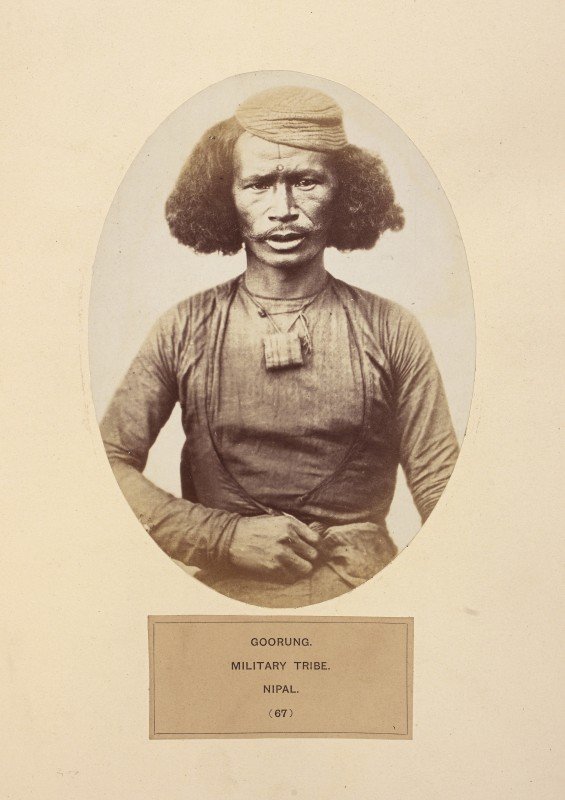

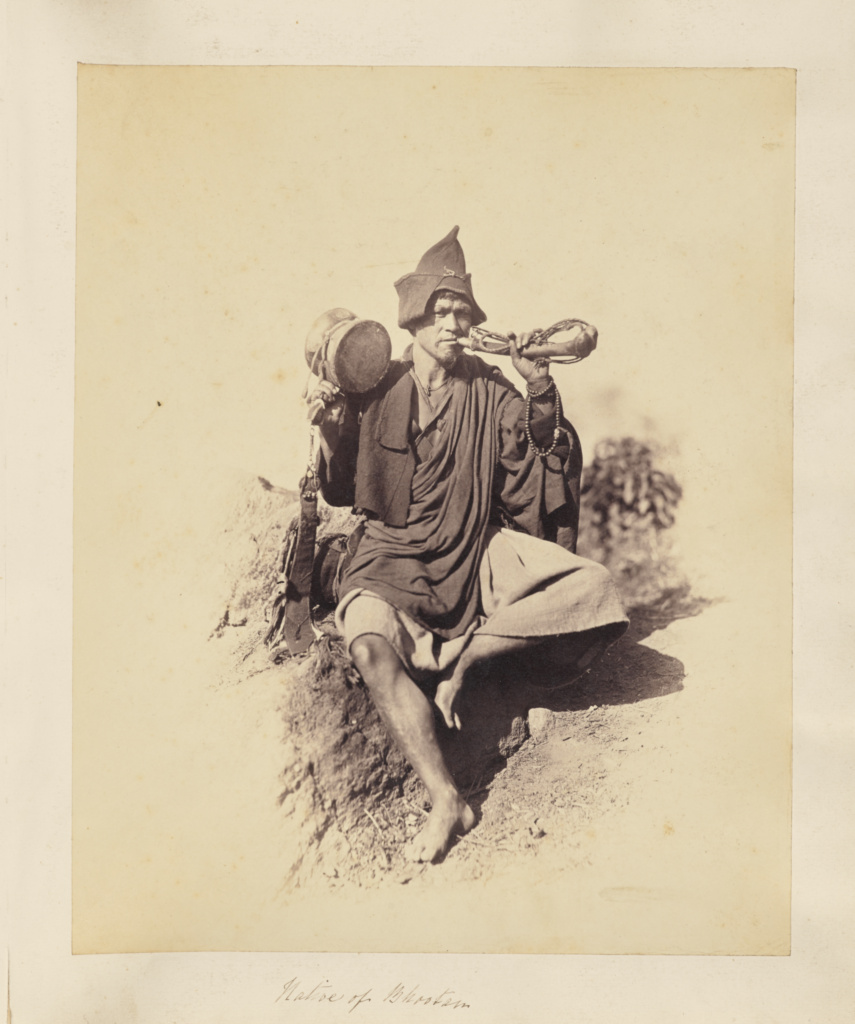

A keen photographer and member of the Bengal Photographic Society. He produced an 80 albumen photograph of ‘Racial Types of Northern India ‘which were displayed and awarded a gold medal at the London International Exhibition in 1862.

Simpson‘s trip to Assam in 1867 – 1868 resulted in his photographs illustrating ‘Descriptive Ethnology of Bengal‘published in 1872. Many of Simpson’s portraits were included in Watson & Kay’s eight-volume “The People of India” (1868-1875). Volumes I and II of the “The People of India” are comprised almost exclusively of Benjamin Simpson’s portraits, each titled according to the subject, tribe, and geographic location.

Simpson produced a series of photographs of Kandahar, Afghanistan during the Second Afghan War of 1879-1880. They were published by Bourne & Shepherd.

He took many photographs of the city and its people in the months following the September 1880 victory in the Battle of Kandahar. Simpson’s images are in Albumen Prints, mounted one to a page and, the majority of glass negatives are signed and numbered by him. He also sometimes edited or repainted his negatives to refine the image.

Albumen prints dominated all areas of photography in India from 1855 until 1890, and variants of albumen photographs were produced until the late 1920s.

Several other major positive photographic processes—glossy Collodion, printing-out paper (POP) Silver gelatin, and developing-out paper (DOP) Silver gelatin—were used during that period, producing photographs that were sometimes visually similar to albumen photographs. A combination of visual, microscopic, and analytical signatures of all of these photographic processes allows for the positive identification of each process.

Albumen paper had to be very thin and of very high quality. If the paper was too thick it would be hard to manipulate while coating and sensitizing, which was done by hand. Thin paper usually mounted to a secondary support.

Most albumen photographs were produced by copy printing a negative on a prepared sheet of sensitized albumen photographic paper. As such, most existing albumen prints have the identical size of the camera-produced negatives. Many untrimmed albumen photographs show a dark border around the prints that reflect the size difference between the albumen paper and the negative from which the photograph was produced in the copy frame.

Whereas most albumen photographs were toned, some, namely test photographs, were left untoned. Depending on the quality of the darkroom processing and their state of conservation, albumen photographs can be found in different color tonalities ranging from very light brown, brown, and reddish brown to dark violet-black.

Most albumen photographic papers were thin and had a strong tendency to curl inside, forming tight rolls of unmounted albumen photographs that, when left in such a state after processing, were rather fragile and difficult to handle without special treatment and conditioning.

Most photographs were mounted on special card stock (CDV, CC, and other formats), paper substrates, mounting boards, or album pages. Sometimes the adhesive resulted in a visible tonality change or bleaching of the albumen prints, causing the lines of applied adhesive to show up in the prints as lighter, well-delineated areas that disfigured, to various extent.

Earlier albumen prints, created before about 1870, were usually less glossy than double-coated albumen photographs. Albumen photographs were made glossy by surface burnishing and varnishing. Preparing albumen photographic papers using aged or partially putrefied albumen also produced higher-gloss albumen prints.

When left unmounted but stored flat underweight, these old albumen photographs can remain flat, clearly showing that the albumen paper substrate was usually very thin. Most old albumen photographs show a certain level of yellowing of the albumen layer. You can read more about the preservation and conservation of albumen prints at https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/atlas_albumen.pdf

Reference

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2317326/?page=1

Beyond Binding: Reconceptualizing Watson and Kaye’s ‘The People of India’ (1868-1875), Farquhar, Jessica Jaeok, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0323w55j

The Library of Congress Afghanistan Project

The Coming of Photography in India, CHRISTOPHER PINNEY, THE BRITISH LIBRARY, 2008